Early in my teaching, I was able to identify when students struggled with numbers. I didn’t have the sophistication or necessary tools to pinpoint exactly where the problem originated, or the gaps that needed filling, but it was glaringly obvious as children dragged their way through math, seeming to fall further behind daily, that something was not right. Because I didn’t have the understanding of mathematics and how children think, my only support for these children was grasping at straws. More practice and more games didn’t improve their number sense, but made the parents, children, and me feel like were trying, and perhaps making some marginal improvement.

Over the years, I have had conversations with many teachers about number sense and place value. What does it mean? What does it look like? What can children do and say when they understand numbers? What do we do when children struggle with numbers? As it turns out, this is a complex topic, that many feel ill-equipped to answer, and researchers struggle to find a common definition. Many teachers rely on the place value skills enumerated in textbooks and older standards. But, does that really mean a child understands numbers? If you teach a child how to compare, order, and round numbers, does this mean they have mastered number sense?

There are a variety of definitions of number sense in the field of mathematics. NCTM (2012) defines number sense as follows:

“Number sense refers to a person’s general understanding of number and operations along with the ability to use this understanding in flexible ways to make mathematical judgments and to develop useful strategies for solving complex problems (Burton, 1993; Reys, 1991). Researchers note that number sense develops gradually, and varies as a result of exploring numbers, visualizing them in a variety of contexts, and relating them in ways that are not limited by traditional algorithms (Howden, 1989).”

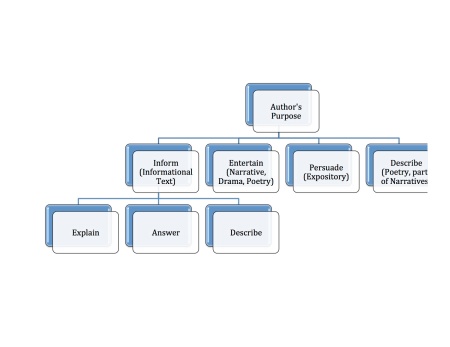

McInstosh, Reys, and Reys (1992) defined number sense as “a propensity for and ability to use numbers and quantitative methods as a means of communicating, processing and interpreting information. It results in an expectation that numbers are useful and that mathematics has a certain regularity (makes sense).” They further delineated their definition with the clear framework detailing number sense below, with the understanding that overlap occurs.

Number Sense

| Key Components |

Student Understandings |

| Knowledge and facility of numbers |

A sense of orderliness of numbers (place value,and relationships and ordering between and among number types)Multiple representations for numbers (symbolic, equivalencies, decomposing, and comparisons)

Sense of relative and absolute magnitude of numbers (comparing to physical and mathematical referent)

System of benchmarks (mathematical and personal) |

| Knowledge and facility with operations |

The effect of operations (whole numbers, fractions, decimals)Mathematical properties

Relationship between operations |

| Applying knowledge of and facility with numbers and operations to computational settings |

Relationship between problem context and computation (exact vs. approximate)Awareness that multiple strategies exist (invent, apply, and select strategies, determining efficiency)

Inclination to utilize an efficient representation and/or method

Inclination to review data and result for sensibility (reasonableness) |

Framework for Number Sense (McIntosh et al. 1992)

McIntosh et al. make it clear that number sense is not just about knowing what to do, but rather, must be entrenched in what makes sense. Thinking must be involved at all levels of working with numbers, and therefore, numbers and procedures cannot be taught in isolation. This framework very much supports the goals of Common Core.

The goals within Common Core, NCTM, and McInstosh et al. are further supported by the goals of mathematical proficiency as defined by The National Research Council. The Council determined five interwoven and interdependent strands of mathematical proficiency. In their report, Adding It Up Helping Children Learn Mathematics (2001), they clarify the importance of depth, clarity, precision, flexibility, and reflection in student thinking as delineated by the strands below:

- conceptual understanding—comprehension of mathematical concepts, operations, and relations

- procedural fluency—skill in carrying out procedures

flexibly, accurately, efficiently, and appropriately

- strategic competence—ability to formulate, represent, and solve mathematical problems

- adaptive reasoning—capacity for logical thought, reflection, explanation, and justification

- productive disposition—habitual inclination to see mathematics as sensible, useful, and worthwhile, coupled with a belief in diligence and one’s own efficacy.

If we reflect upon how number sense is defined, then what does number sense look like? Students with strong number sense can subitize easily, understand magnitude (relative size of numbers), have established cardinality, can strategically decompose (break down numbers) to make computation easier, understand the importance of ten within our number system, understand number relationships, and have proportional reasoning. They determine the efficiency of their strategies, the reasonableness of their answers, and understand the application and context within which operations are used. These concepts cannot be taught in one lesson or unit. They are ongoing experiences students need as part of their math education throughout the grade levels. When students emerge from classrooms focused on these concepts, they come to understand that math is about relationships, not memorization, and flexibility rather than rigid rules.

Therefore, number sense entails far more than the traditional chapter on place value. Proficiency cannot be measured by a skill set, or regurgitation of memorized procedures and rules. Students need dynamic experiences with numbers. They need to be able to dive into the depth of numbers, explore their uses, their flexibility, their application, their differences, their nuances, and their reason. And, while numbers are both abstract and concrete, they need to be seen as something that makes sense. Ultimately, learning mathematics must be with understanding. When we present math as a series of rules and explain to children how to follow a procedure step-by-step, we have actually robbed them of the opportunity to develop both number sense and mathematical proficiency. As this is how our system is designed, many children receive passing grades throughout school, only to falter later on, finding there is no solid foundation to support more advanced mathematics. Common Core is calling us to change our practices so that children emerge from the classroom as mathematical thinkers that demonstrate the ability to adapt to the ever-changing world awaiting them, rather than as mini-calculators with an isolated set of memorized skills.

Kilpatrick, J., Swafford, J., & Findell, B. (2001). Adding it up : helping children learn mathematics / Mathematics Learning Study Committee, Center for Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, National Research Council ; Jeremy Kilpatrick, Jane Swafford, and Bradford Findell, editors. Washington, DC : National Academy Press, c2001.

Mcintosh, A., Reys, B. J., & Reys, R. E. (1992). A Proposed Framework for Examining Basic Number Sense. For The Learning Of Mathematics, (3), 2.

NCTM (2012). Illuminations. Cited on December 30, 2012 from http://illuminations.nctm.org/Reflections_preK-2.html.